Growing Roots:

Understanding Community Housing Needs of Refugee Populations in Surrey

-

Surrey, once one of the most affordable Lower Mainland cities, now has a scarcity of accessible rental housing, limiting options for low-income tenants, including refugees. Despite this, it hosts a disproportionate number of refugees compared to other Metro Vancouver municipalities. Newly arrived Government-Assisted Refugees (GAR) and refugee claimants face language barriers, unfamiliarity with housing tools, discrimination, and limited rights knowledge, making them vulnerable to exploitation and homelessness.

Through this project, we gathered the stories of four refugee communities: Spanish-speaking refugee claimants from Latin America, Dari-speaking Government-Assisted Refugees (GARs) from Afghanistan, Swahili-speaking GARs from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Arabic-speaking GARs from Syria and Lebanon. Over the course of one year, City in Colour Cooperative, in partnership with DIVERSEcity Community Society, engaged with these four groups to document their housing experiences and their diverse journeys from their arrival to Canada to their current homes.

The main goal of this project is to understand and map out the systemic barriers that hinder refugees and refugee claimants from securing adequate, affordable, and long-term housing in Surrey, while raising awareness about their housing situation.

We used trauma-informed, art-based, and participatory methods for this project.

Arts-Based Method: We began with an art-based workshop to explore the idea of home and current housing situations, allowing diverse participants to express their experiences creatively. The visual representations and testimonies are shared below and were also shared in a public exhibition.

Trauma-Informed Design: We ensured our sessions were safe and non-oppressive, avoiding re-traumatization. The Pacific Immigrant Resource Society reviewed our designs, and we had trauma-informed practices sessions with a psychologist and a student counselor available.

Participatory Approach: We collaborated with four communities, engaging a total of 43 participants, including nine co-researchers with lived experience, to explore topics from focus group sessions in greater depth and review educational housing documents together.

In the following sections, we will explore various aspects of this project. We begin with a preface by Natalia Botero, a photojournalist in refuge and one of the community co-researchers for the study. Next, we delve into three sections that examine participants' ideas and experiences concerning ideal home situations, current housing conditions, and their housing journeys, presented through mixed media and participants' quotes. Finally, we conclude with our findings , recommendations and next steps.

-

Solid State Community Industries, a non-profit building worker co-operatives with racialized migrant families in Surrey, provided unwavering support. They opened their space for workshops, co-research meetings, office use, and storage, while also facilitating community connections, logistics, and knowledge mobilization.

DIVERSEcity Community Resource Society, a settlement organization in Surrey, was a key partner throughout the project. They advised on the project design, helped with outreach to diverse language groups, and connected us with relevant organizations for research dissemination. Their continued support in facilitating refugee outreach and sharing our findings with stakeholders was invaluable.

The Black Arts Centre, an artist-run community space in Surrey, hosted our group sessions and gallery exhibit from July to August 2024. This anti-oppressive space provided the perfect setting for delicate conversations about housing. BLAC also played a crucial role as a knowledge mobilization partner, promoting our gallery exhibit and events.

-

The Growing Roots project has been funded by the Real Estate Foundation of BC and the Community Housing Transformation Centre.

A foreword by lived-experience co-researcher Natalia Botero

-

The empty house with open doors, half-open windows and a table served. Abandoned land, the crops alone, and our animals waiting for a call to be fed. Each of us migrants in refuge began an uncertain path far from everything that gave us confidence, but at the same time far from all the violence that caused us the pain of running away from our countries. We arrived in a country which we only knew was to the north, cold, and where a language other than ours was spoken. How, where, and in what way to get there was always our great uncertainty. Our goal was to find a home to give our children the security and tranquillity we did not have in our countries. Our goal: to settle in a place called home.

When we were invited to participate in the “Growing Roots” workshop, none of the participants knew the reality of the others. We were four groups of Refugee Claimants and Government Assisted Refugees from Latin America (Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico), Afghanistan, Congo, Syria, and Lebanon. For more than a year, we shared our experiences, our life stories, and faced the realities of migrating to Canada. We were families with a father, mother and several children, single mothers with three children, or entire families with grandparents and nephews, and young people with only their backpacks. In the experience of sharing and talking about our housing reality in British Columbia, we understood the crude and complex situation that each one is going through; abused by the landlords, with precarious economic situations, without language skills, cornered in bad places, unsafe conditions, in which our mental and emotional health, and that of our families, deteriorates more and more. All of this from not having a place called Home.

Many of us arrived at different places in emergency conditions; shelters, temporary hotels, an inflatable mattress for four people in a rented room, the house of an unknown family to sleep in the living room, a basement with 12 migrants that we did not know. If we were lucky we might have enough to pay a few days in a motel. During the months and years that we have had to travel the streets of Canada in search of a place to live, it has not been pleasant, friendly, easy or safe. We live under constant worry of not being able to give our families a safe space where they can build a reliable and stable life, a place they can call Home.

None of us arrived knowing the rental system. We didn't know how to get a place to live, so we went out to walk the streets and look for signs for rent. That's how we did it in our countries, but here it is very different. Our daily path has been full of barriers, setbacks and disagreements, on the one hand, the pressure of our families wanting a place that provides shelter on the other hand, trying to keep everyone united and looking for the right conditions on a day-to-day basis. We have had to learn to fish without a hook, to build the route to get to our house. After several months, we discovered that many of the contracts we signed were not legal, and had their quirks and abuses, such as illegal or unreasonable restrictions from the Landlords. We didn’t our rights as tenants, nor did any of us know what we were facing for not having a rental history, knowledge of the documentation, and enough money to rent a decent and safe place that we could call Home.

The responses to our needs from the Government and organizations involved in our settlement have been disjointed, vague and distant. Although there are some normal requirements, there are so many obstacles to finding safe housing. When we arrived at the Border or when we presented ourselves at immigration, no one asked us what our housing situation was, or how they could help. They did not offer any options to make our arrival smoother and safer, or how to work together so we can find that place called Home.

In each of the pieces produced in the workshop, in each of our conversations, in each of our tears and each of our smiles there is resilience. Our dreams, our desires, and our frustrations are captured. We did not choose to leave our country by our own will; the violence of the war forced us to save our lives. We lost our Home, our families and friends. Today, here, we just want to build, hand in hand with everyone, a safe, friendly, happy place called HOME.

Over the course of four group sessions, we invited participants to express their thoughts and emotions about their 'ideal' home using mixed media art methods. Each participant was asked to utilize paint, collage, drawing, and colour to depict, in their own way, their concept of an 'ideal home'. Below, we have selected nine of these artworks, each accompanied by a quote or explanation from the participant.

-

In all the Spanish, Dari, Swahili, and Arabic groups, participants shared similar visions of home. The Spanish speaking participants saw home as a refuge for peace, tranquillity, and community, where laughter, music, play, and togetherness freely flow. Nature, symbolized by trees and plants, held significant meaning, representing protection, life, and reciprocity. Similarly, the Dari-speaking participants viewed home as a sanctuary, a place of belonging, warmth, and tranquility, nurtured by connections with friends and loved ones. Shared meals formed bonds within a safe and closely-knit circle, enhancing the sense of belonging and creating an atmosphere of peace and freedom.

In the Swahili-speaking group, the themes were also centered around greenery, trees and fruit forests, the sun and moon, living in nature, walking dogs, herding cows, and listening to birds singing. Similar to the Afghan community, food was also an important element for the Swahili community when discussing the concept of home. Sharing food, unity at home, and love for family were concepts related to that. Neighbourliness, connecting with neighbours, and fellow citizens in church were also brought up.

In Arabic-speaking groups, participants exchanged visions for their ideal homes. For them, home in their native country represented peace, a united family, and a source of pride. They had space, potted plants, privacy, and beauty. All of the participants described having to flee "home," meaning both their native country and their residences. They spoke of their previous homes with pride and nostalgia for a past that won’t return.

Similarly, during these eight group sessions, we invited participants to depict their current housing conditions to contrast with their 'Ideal Home'. Below, we have selected nine of these artworks, each accompanied by a quote or explanation from the participant.

-

Participants from all groups expressed common concerns regarding their housing situations. The Spanish participants highlighted a prevailing sense of despair and abuse, facing high prices and challenging living conditions that restricted their freedom and subjected them to humiliation, discrimination, and economic distress. Similarly, the Dari group voiced worries about health, cleanliness, safety, security, and maintenance, alongside significant financial challenges. They grappled with high rent and irregular increases, limited income assistance or low-paying jobs, constant fear of eviction, high utility expenses, unrealistic rental reference requirements, security concerns, and issues like mold and rodent infestations, all of which compounded their housing struggles.

Participants in the Arabic-speaking group described their current housing situation with less passion compared to their thoughts about ideal home, perhaps an experience rendered bitter by the search process and the unhappiness and anxiety of their kids. Some are feeling isolated, while others try to remain hopeful. All suffer from unfair and sometimes discriminatory landlord practices. While some know their rights, they’re reluctant to pursue them—perhaps due to exhaustion or a sense that their efforts would be futile.

Themes from Swahili speaking participants include high expenses, cramped housing conditions, and unattainable housing requirements set by landlords. Lack of work and career support, and a need for advocacy were also mentioned . Additionally, they expressed concerns about access to education and limited access to health services and doctors.

The housing journey for Government Assisted Refugees and refugee claimants varies significantly. In the following sections, we delve into their unique experiences.

-

Both GARs and refugee claimants face significant challenges rooted in trauma, displacement, and the stress of starting over in a new country. Despite these shared difficulties, their experiences differ due to varying levels of support and pathways to settlement.

A common thread between the two groups is the profound emotional and psychological impact of their journeys. Both endure the loss of loved ones, homes, and their homeland, resulting in trauma that lingers as they attempt to rebuild their lives. They also face similar barriers to housing, including discrimination, a lack of references, and limited knowledge of tenant rights, which often force them into substandard and overpriced accommodations. Cultural misunderstandings and systemic challenges, such as language barriers and unfamiliarity with Canadian systems, further exacerbate their struggles. Exploitation by landlords is another shared issue, with illegal evictions, demands for excessive advance payments, and refusal to return deposits undermining their security and stability.

However, differences emerge in the level of support each group receives upon arrival. GARs are provided with structured support, including welcome packages and temporary accommodations in hotels for 2-3 months, offering some initial relief. In contrast, refugee claimants face a less systematic process and are often left to navigate settlement services independently, receiving only occasional referrals from immigration officers.

These differences also manifest in their housing pathways. GARs typically transition from temporary hotels to searching for long-term housing. However, delays in securing accommodations can result in reliance on shelters. In contrast, refugee claimants often face "hidden homelessness" upon arrival, frequently moving between emergency shelters and temporary housing for extended periods—sometimes exceeding 10 months—before attaining stability.

Access to resources also varies. GARs benefit from more structured initial supports, yet still encounter challenges such as long wait times for English classes and difficulty navigating the housing market. Refugee claimants face even greater obstacles, as delayed paperwork prevents them from accessing housing, jobs, and language programs, leaving them in a more precarious position.

Findings

-

For refugee claimants, the limited or lack of support upon arrival means they spend many months staying in precarious housing. This period of unstable housing affects their possibility of moving forward and finding jobs. This period could last more than 10 months.

-

During their stay in shelters, temporary housing, or hotels, participants reported feeling lost, with little to no guidance on how to navigate the housing system. Government-Assisted Refugees (GARs) and refugee claimants often lack familiarity with housing navigation processes, as well as their rights and responsibilities as tenants.

-

Most participants in this study currently live in private rental market units. At the time of the study only 2 out of 43 participants were living in social housing. Many participants mentioned the long BC Housing waitlist and their disappointment about not being able to live in a social housing provided by BC Housing.

-

The “Canadian“ definition of family is primarily nuclear, but for refugees and newcomers, the concept varies significantly. It can include cousins living together and raising a child, multi-generational households, or even chosen families. In contrast, BC Housing defines a family as consisting of parents with dependents—children under 19, full-time students under 25, or dependents accepted by the Canada Revenue Agency (BC Housing, BCHousing ProgramFinder). This strict definition excludes non-traditional family units that are common among refugees and newcomers, creating significant barriers for them when trying to access social housing. These rigid eligibility criteria limit the ability of these communities to secure stable housing, compounding the challenges they already face.

-

Most participants spend nearly all their income assistance on rent, with the majority allocating over 70% of their income to housing. Participants with large families often spend more than 95%, leaving little for other essentials. Given the high cost of groceries and basic necessities, these families face immense financial pressure and must rely on food banks to meet their needs.

-

Participants highlighted that landlords’ abuse is also financial, including charging high rents for unfit suites, demanding cash payments or several months' rent upfront, withholding deposits, and refusing to provide receipts.

-

Participants shared that they feel restricted in their homes, especially when landlords live nearby. They mentioned being unable to let their children play or invite guests. In some cases, landlords even monitor their use of electricity, sending messages instructing them to turn off lights or appliances. Some participants were threatened with eviction unless they stopped cooking their traditional foods, which landlords deemed to have an unpleasant smell. These requests are unlawful under the BC Residential Tenancy Act, which protects tenants' rights to quiet enjoyment and freedom from discrimination.

-

Participants also shared that they live in unfinished or outdated suites in need of repairs. In some cases, landlords neglect maintenance requests for months. Many participants reported health issues caused by mice and rat infestations. Others expressed safety concerns, mentioning thefts from their properties.

-

Participants overwhelmingly expressed frustration with their inability to find employment, as securing a job would provide economic stability and access to better housing. Their job search is hindered by a lack of referrals and connections, language barriers, deskilling, and the lengthy, complex process of validating their educational credentials, all of which compound the challenges they face.

Project Reflection

From these findings, it is clear that the current system leaves refugees and refugee claimants living in poverty, exposed to abuse, oppression, and, in some cases, exploitation.

It is essential to improve the reception system to help refugees transition smoothly into employment and rebuild their lives with dignity. Some necessary changes include reducing wait times for documentation and providing access to permanent addresses.

Our conversations revealed that under the current system, most government financial assistance for refugees is directed toward private landlords, effectively increasing private wealth. This funding could be better allocated toward developing affordable housing stock that remains protected over time.

Furthermore, there are no effective mechanisms in place to protect tenants from abusive landlords. Many tenants feel fearful and lack sufficient knowledge about their rights. Alongside the creation of more affordable housing, it is crucial to establish mechanisms to protect vulnerable tenants.

We believe a shift toward a human rights-centered housing approach is essential—one where tenants have meaningful protection against eviction, harassment, and threats. Housing should be affordable enough not to compromise other basic needs, and policies should support cultural identity and diversity in housing options.

-

City In Colour Cooperative, in partnership with DIVERSEcity Community Resources Society, is currently undertaking the next phase of the study titled "Growing Roots: Refugee-Centric Housing Solutions in Metro Vancouver," funded by the Real Estate Foundation of BC.

The project builds upon the insights, methodologies, and collaborative model developed in our previous initiative, "Growing Roots: Understanding Refugee Housing Needs in Surrey, B.C."

The primary goal of this phase is to collaborate with refugee co-researchers to review national and international affordable housing case studies, formulate policy recommendations, and develop Refugee-Centric Design Guidelines for Housing. These guidelines will include recommendations and solutions for policy changes that address the specific housing needs of refugees and refugee claimants.

Our intention is to share the guidelines with community partners, stakeholders, and various levels of government, with the hope of improving the precarious housing situation faced by the target population.

Collaborative Solutions and Strengthening Co-Researchers' Capacity

A major success of the project was the strengthening of our co-researchers' capacities while collaboratively working on solutions. Growing Roots' co-researchers led various workshops and events, including the "Rent 101" workshop, which was conducted by our Spanish-speaking co-researchers. This workshop fostered connections and empowered participants by sharing practical housing information in Spanish, drawing from their lived experiences. With ten attendees, it effectively addressed critical needs by aiding in securing permanent housing and encouraging connections among Spanish-speaking refugee claimants. Additionally, Dari-speaking Afghan co-researchers collaborated with the CIC to host the Afghan Spring Gathering and Eid Celebration, combating social isolation while developing valuable event-planning skills. Together, these initiatives exemplified the project's commitment to enhancing the capacities of co-researchers and supporting their communities.

-

Rent 101: A peer-led housing rights and navigation workshop in Spanish for refugee claimants.

The peer-led housing rights and navigation workshop for refugee claimants originated from City In Colour Cooperative’s Growing Roots Project: Understanding Community Housing Needs for Refugees in Surrey. Facilitated by two Spanish-speaking refugee claimants and community co-researchers, the three-hour workshop combines educational and social aspects. It aims to share practical housing information in Spanish, drawing from participants' lived experiences. This workshop addressed the critical needs of refugee claimants by assisting them in searching for permanent housing and fostering connections among Spanish-speaking refugee claimants. It is structured into two sections, with each 45-minute session including a presentation, a question-and-answer segment, and a lunch break for socializing.

Facilitators: Viviana Riascos and Natalia Botero

T book a RENT 101 workshop in Spanish with Viviana and Natalia, contact Natalia: nataliaboterophotographer@gmail.com

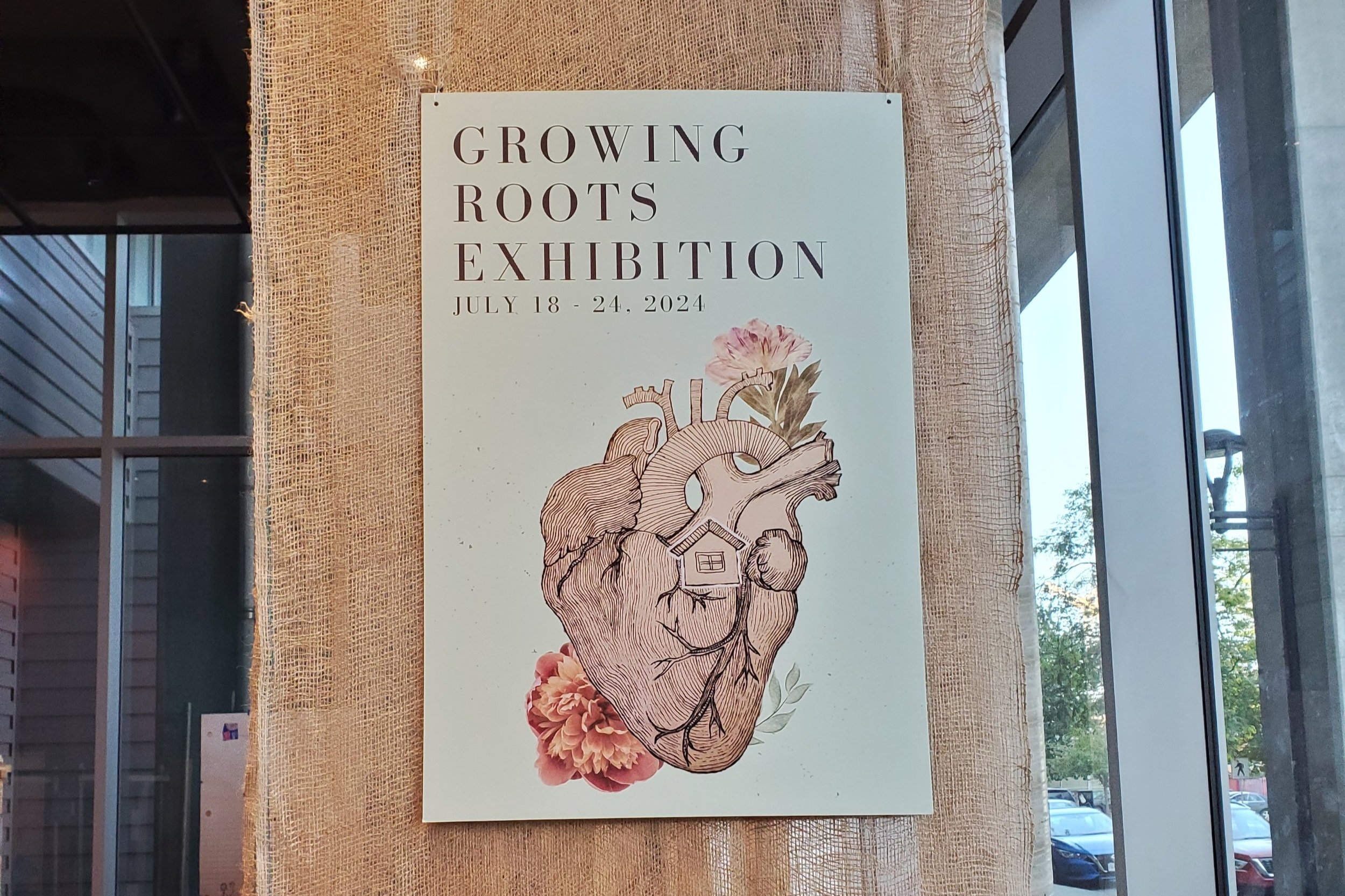

Growing Roots Exhibition 2024

Our first-ever art exhibition exceeded expectations, running longer than planned, from July 18 to the end of August 2024 at the Black Arts Centre in Surrey.

The exhibition attracted significant attention, including media coverage from Surrey Now-Leader and The Tyee. Notable articles like “Growing Roots: Art Exhibit Showcases Refugee Struggles in Surrey” and “For Refugees in Surrey, a Harrowing Search for Housing” highlighted the project’s impact.

Co-curated by Fiorella Pinillos and lived experience co-researcher Natalia Botero, the exhibition featured Natalia’s contributions both as a photographer for four of the pieces and as the author of the exhibition's prologue. The display included participants' artwork and quotes, a section on the housing journey, four highlight stories, and a multimedia installation by artist Arshi Chadha. Inspired by the project, Arshi's installation incorporated video recordings from one of our art sessions.

Our Commitment to Indigenous Peoples and Reconciliation

City in Colour Cooperative recognizes that the land in which this study takes place is on the ancestral, traditional and unceded territories of the SEMYOME (Semiahmoo), q̓ic̓əy̓ (Katzie), kʷikʷəƛ̓əm (Kwikwetlem), q̓ʷɑ:n̓ƛ̓ən̓ (Kwantlen), qiqéyt (Qayqayt), xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) and sc̓əwaθən məsteyəxʷ (Tsawwassen) First Nations.

Our project is committed to advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples and fostering reconciliation through respect, cooperation, and partnership. We align with UNDRIP Article 15 by incorporating land acknowledgments at all events and ensuring that project staff and co-researchers are educated on the history and culture of the host Nations. We emphasize the importance of building connections between newcomers and Indigenous Peoples by addressing shared experiences of displacement, exclusion, and resilience.

We also integrate Indigenous history and cultural awareness into our engagement sessions, with a focus on educating newcomers—many of whom may be unfamiliar with these issues.

These resources were created by the Surrey Local Immigration Partnership (Surrey LIP) in collaboration with the Fraser Region Aboriginal Friendship Centre Association (FRAFCA) to address misconceptions about Indigenous people. They provide accurate information on the historical and current experiences of local Indigenous communities.